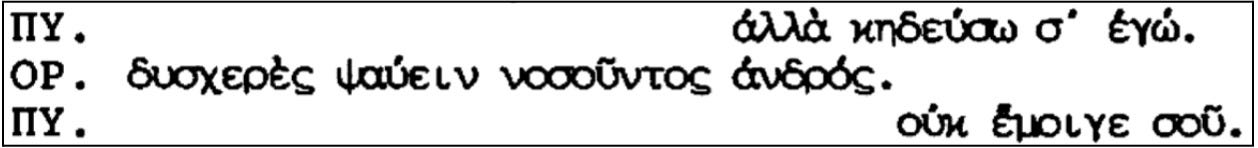

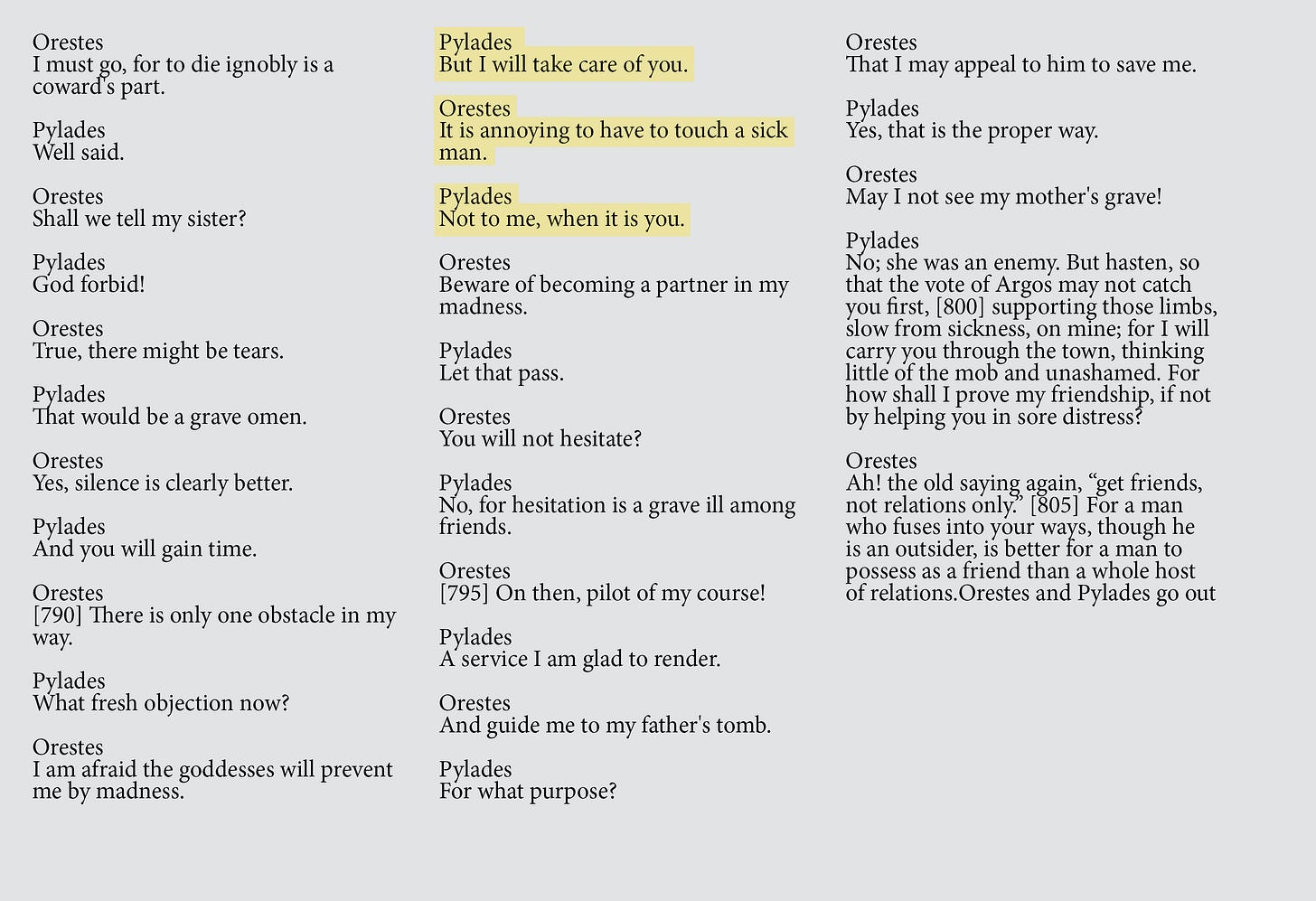

A few weeks ago I ran across an Instagram post with nine different translations of the above exchange from Euripides’ play, Orestes (408 BCE). The different versions fascinated me because depending on the translation, the dialogue can read romantic, platonic yet utterly devoted, or boring and unconvincing. It’s fun to line these up side by side and analyze the choices each translator made, and judge their effectiveness. Below, I’ve reviewed and rated each translation from an even longer list of fifteen (I had to create a Tumblr account to access this), which as far as I can tell is the original compilation. But first, here is a longer section of the E.P. Coleridge 1910 translation for context if you want it.

Anne Carson (2009), 7/10: “Rotten” is throwing me for a loop - I can’t tell if I like it. Regardless, the whole thing reads a little too soapy, I think. It’s giving Shonda Rhimes.

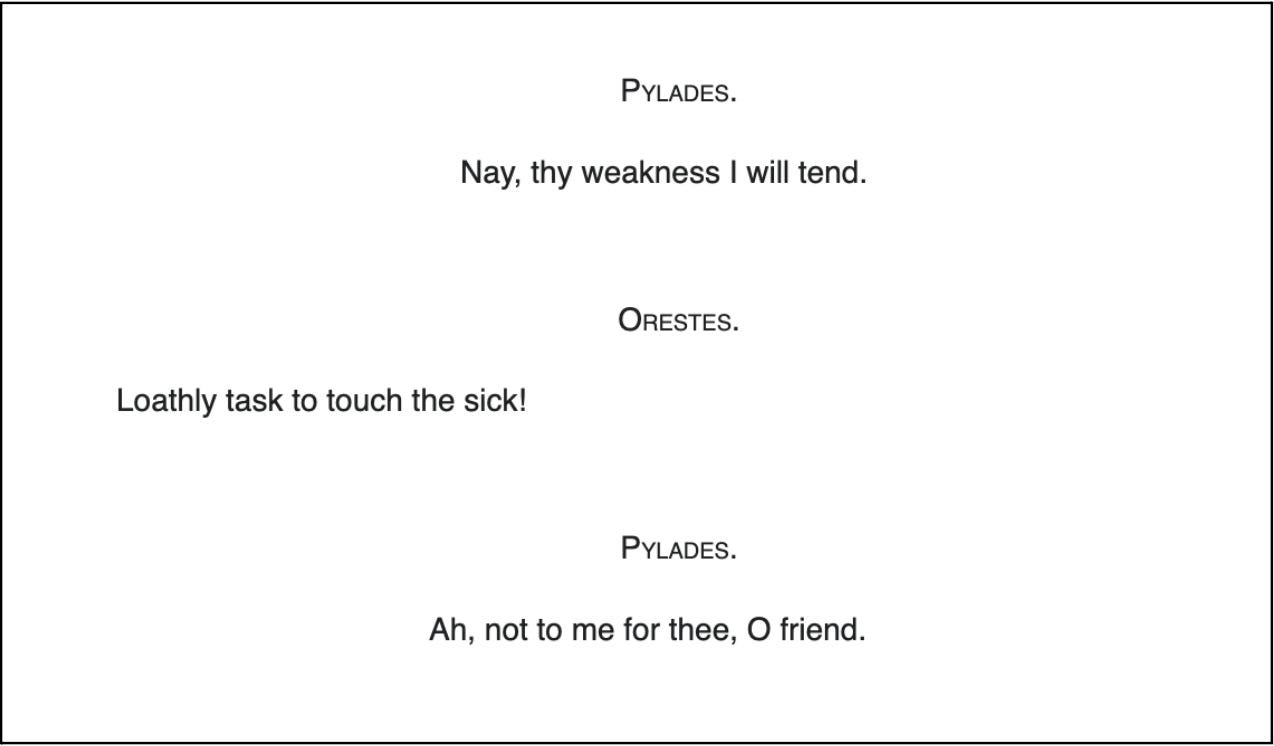

Arthur S. Way (1898), 6/10: I imagine this would be highly dependent on delivery. I like the “Nay” and the “Ah” and the casual air of the last line. The exclamation point I could do without.

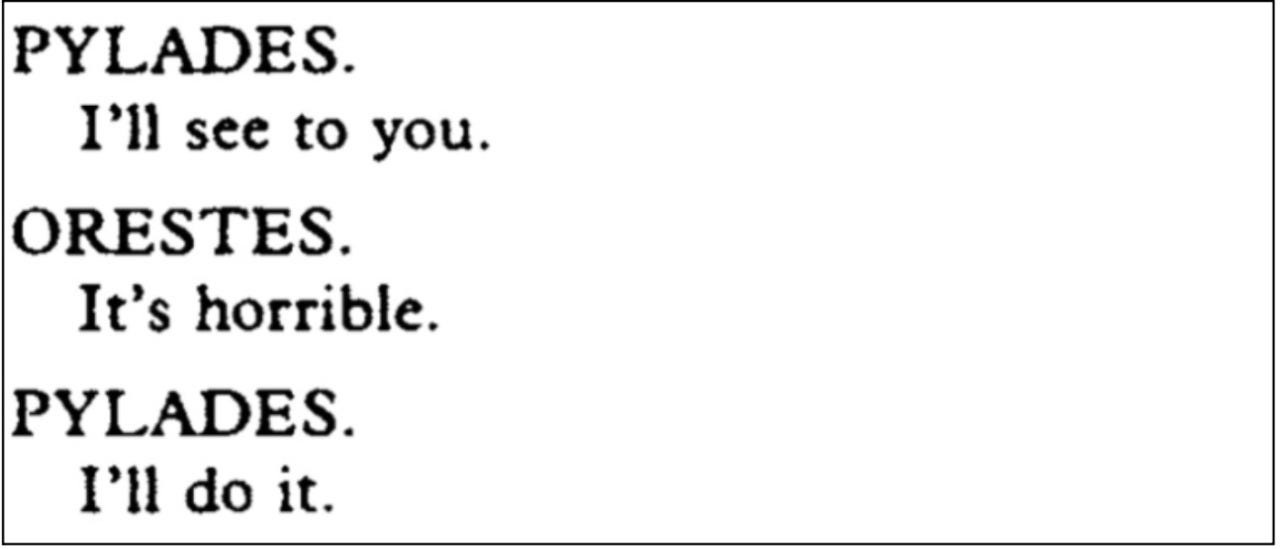

Theodore Alois Buckley (1892), 3/10: Ending the first and last lines with “thee” is unsatisfying. So sterile.

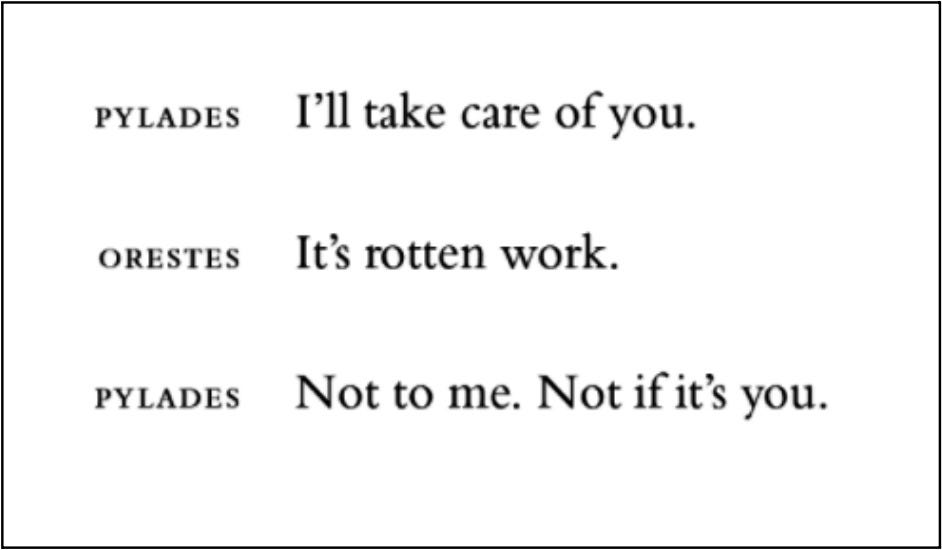

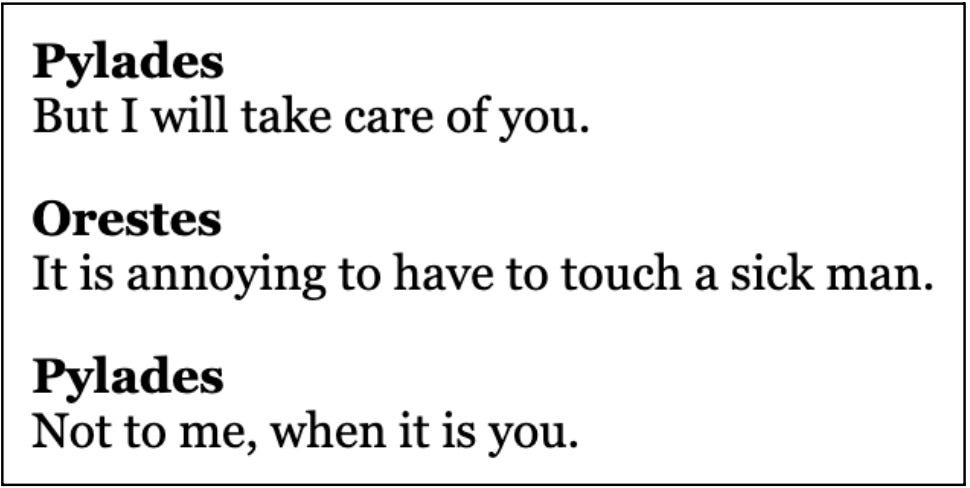

Kenneth McLeish (1997), TEN OUT OF TEN: It feels like a realistic dialogue, while also carrying the perfect amount of weight in each word. Kenneth cut the bullshit and gave us the ESSENCE of the moment. Beautiful.

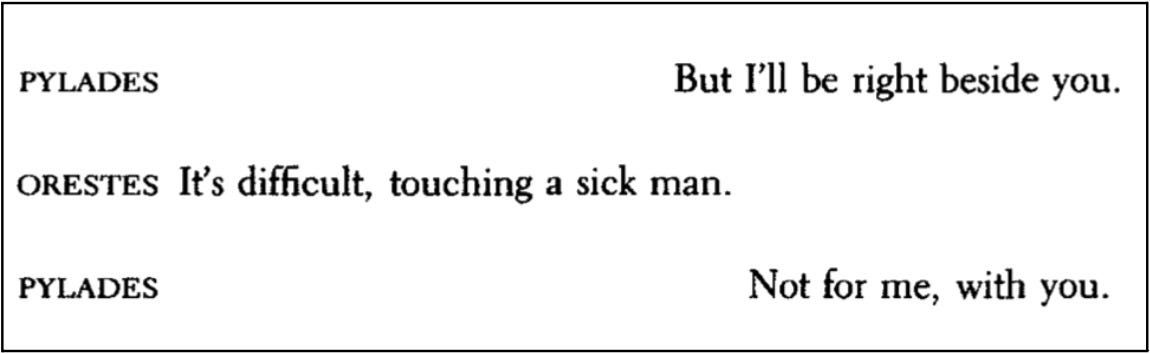

John Peck, Frank Nisetich (1995), 5/10: “Difficult” isn’t quite hitting the mark for me. It reads like the lines were translated in isolation, rather than as a conversation. (That is a common complaint I have with many of these, but I only just thought of it reading this one.)

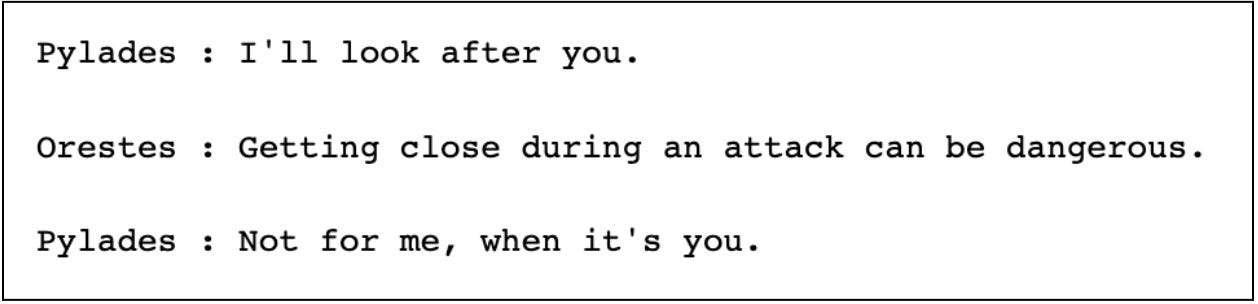

Andrew Wilson (1993), 2/10: This doesn’t even make sense. The important part of the exchange is Pylades assuring Orestes that he wants to care for him. “Not for me, when it’s you” makes sense in response to concern of annoyance or disgust, not something as objective as danger.

George Theodoridis (2010), 2/10: Almost identical to McLeish’s interpretation, but so wordy it loses all effect. Why is “if that happens” necessary when we’ve already established this is a hypothetical scenario. Extremely unsatisfying.

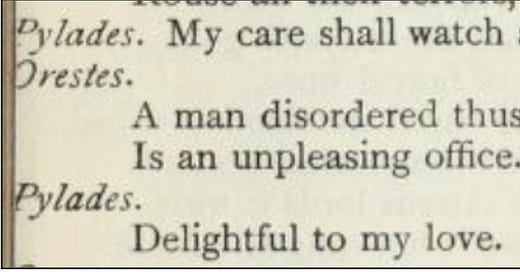

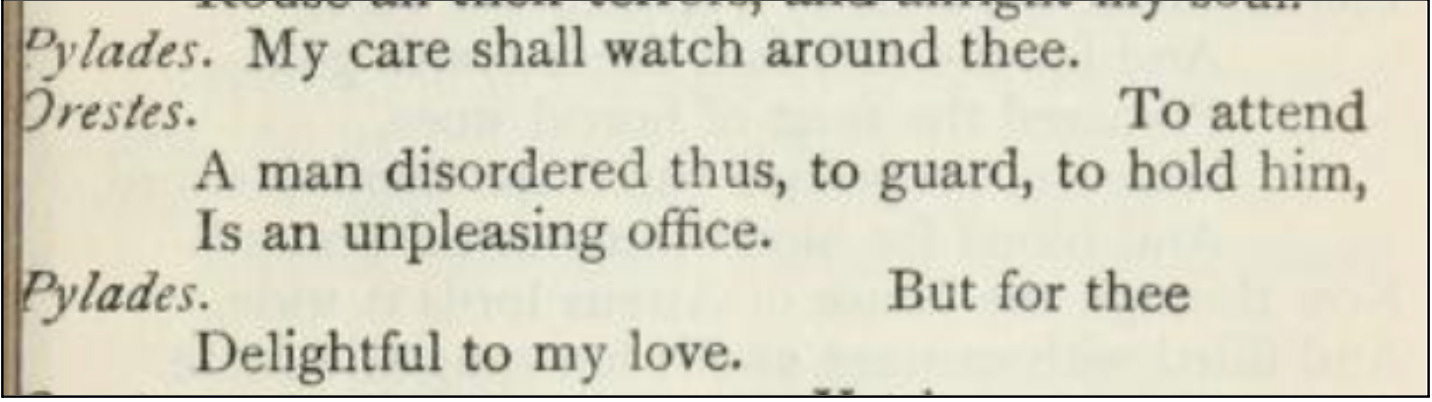

E.P. Coleridge (1910), 6/10: I like the rhythm of the last line, but overall it is boring.

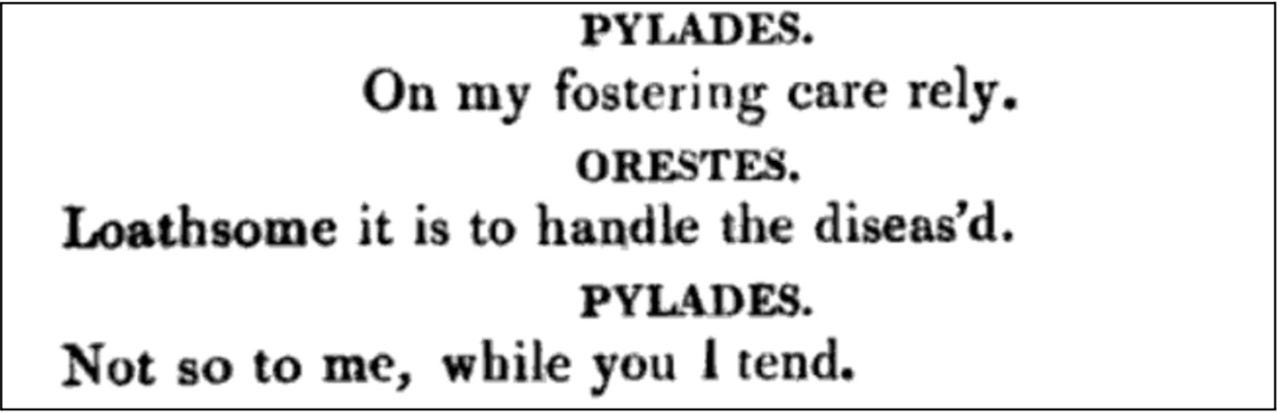

Michael Wodhull (1782), 8/10: “On my fostering care rely” ugh, beautiful.

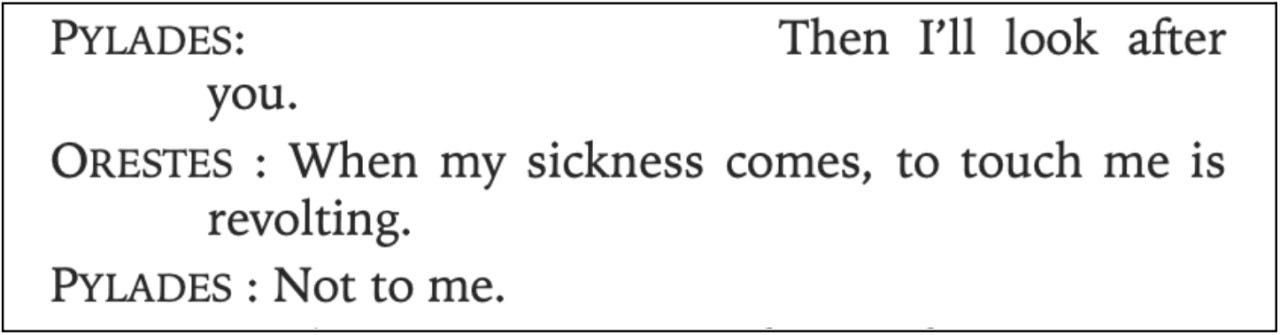

Philip Vellacott (1972), 6.5/10: “Revolting” is good, and starting with “then” gives the dialogue a realistic flow. I don’t mind this one.

R. Potter (1906), 7/10: Awkward but charmingly unexpected word choice. A little Shakespearean for my taste.

M. L. West (1987), 3/10: “In contact with”??? Where’s the flavorrrrr??

Ian C. Johnston (2010), 4/10: Again, BOR-ING.

William Arrowsmith (1958), 9.5/10: Another loose interpretation with excellent flow. I like this one because I can imagine Pylades giving a little smile with that last line. The “hands”-”handle” call and response maintains the dialogue’s central meaning, but gives it the air of banter, letting us infer the closeness of their relationship rather than stating it outright.

Anyways,

Hope y’all have been doing well. It turns out moving involves a lot of little tasks to accomplish and a lot of big feelings of doom to deal with. Writing has been hard. Work has been annoying. I’ve been willing the leaves to drop all summer and they’re still as green as ever, yet Saturdays seem to come and go quicker than I can manage.

Until next time,

Jordan